“我们正处在一场国际汇率战争之中,全球货币正普遍走软。这对我们构成了威胁,因为它削弱了我们的竞争力。”巴西财政部长吉多•曼特加(Guido Mantega)的这些抱怨完全可以理解。在需求匮乏的时代,储备货币的发行国实施扩张性货币政策,而非发行国则以干预汇率作为回应。而那些既不属于前者、也不愿效仿后者的国家(比如巴西)则发现本币大幅升值。其后果令它们担忧。

发生这种汇率冲突并不是第一次。25年前,也就是1985年9月,法国、西德、日本、美国与英国政府在纽约的广场饭店(Plaza Hotel)举行会议,达成了共同诱导美元贬值的协议。更早一些时候,在1971年8月,美国总统理查德•尼克松(Richard Nixon)实施了“尼克松冲击”措施,包括征收10%的进口附加税,并结束美元与黄金的相互兑换。上述两件事都反映出美国渴望美元贬值。今天,美国仍然怀有同样的渴望。但这一次的情况有所不同:关注焦点已不再是日本这样恭顺的盟国,而是下一个全球超级大国——中国。两强相争,很容易伤及围观者。

有三大因素,与眼下的汇率战争相关。

首先,由于这场危机,发达国家正蒙受需求长期匮乏之苦。全球6大高收入经济体——美国、日本、德国、法国、英国与意大利——中,没有一个国家今年第二季度的国内生产总值(GDP)恢复到2008年第一季度的水平。与以往的趋势水平相比,这些国家目前的经济增速至多降低了10%。供应过量的一个信号,是美国与欧元区的核心通胀率已经降至1%左右:通货紧缩正在向我们挥手致意。这些国家希望实现出口拉动型增长。贸易逆差国(例如美国)和顺差国(例如日本、德国)都是如此。然而,整体来看,只有新兴经济体转向经常帐户赤字,才有可能实现这一目标。

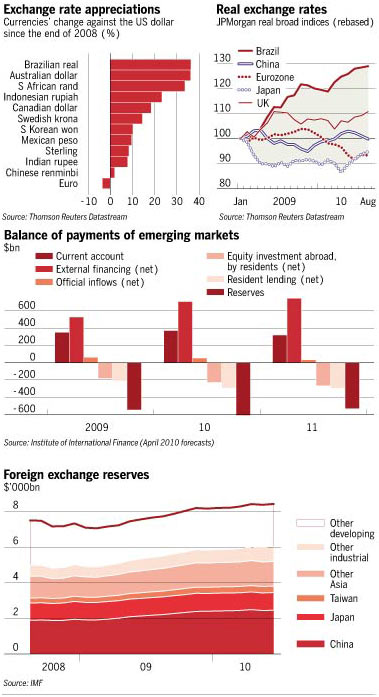

其次,私人部门正在朝这个方向运转。华盛顿国际金融研究所(Institute for International Finance)在4月份的预测中指出,今年净流入新兴国家的外来私人资金将达到7460亿美元(见图表)。这些新兴国家净流出的私人资金为5660亿美元,能够部分抵消上述流入。尽管如此,由于新兴国家还有着3200亿美元的经常账户盈余以及适度的官方资金流入,在没有政府干涉的情况下,新兴国家仍将实现5350亿美元的外部收支盈余。但若不加干涉,这种情况也不可能发生:经常账户必须平衡资本净流动。调整将通过提高汇率进行。最终,新兴国家将出现经常账户赤字,来自高收入国家的私人资金净流入,将为这种赤字买单。事实上,这正是我们所期待发生的。

中国绝对是最明显的干预者:自2009年2月以来,占到了这些外汇累积的40%。到2010年6月,中国外汇储备达到了2.45万亿美元,占全球总量的30%,在其国内生产总值(GDP)中所占比例,攀升到了50%的惊人水平。这种累积肯定会被视为一种巨额出口补贴。

在人类历史上,从来没有一个超级大国的政府,会借给另一个超级大国这么多钱。一些人辩称,这种汇率管理方式不是操纵(与美国国会的观点相左),因为调整可以通过“国内成本与价格的变动”进行。周二出版的英国《金融时报》上,就刊登了美国西部信托公司(Trust Company of the West)科玛尔•斯里库-马尔(Komal Sri-Kumar)的类似观点。如果不是因为中国下了力气、并成功遏制了其干预行为自然会导致的货币及通胀影响,那么,这种论点会更具说服力。与此同时,新兴国家向着经常账户赤字方向、不可避免的调整,正转移至那些对资金流入具有吸引力、同时又不愿(或无力)对外汇市场实施必要规模干预的国家。可怜的巴西!甚至,我们可能正目睹又一场新兴市场金融危机的发令枪响起?

众所周知,尼克松时期的财政部长约翰•康纳利(John Connally)曾告诉欧洲人,美元是“我们的货币,但是是你们的问题”。中国也作出了同样的回应。由于没有作出汇率调整,我们正看到某种形式的“货币战争”:本质上,美国正寻求让中国通胀,而中国则试图让美国通缩。双方都坚信自己是对的;但都没有获得预期的效果;世界其它国家则受到了牵连。

不难看出中国的观点:它正不顾一切地避免自己心目中日本在《广场协议》(Plaza Accord)后的悲惨命运。当初,由于汇率飙升损害了出口竞争力,加之美国强迫其削减经常账户盈余,日本选择了规模巨大的货币扩张,而不是亟需的结构性改革。随之产生的泡沫,促成了上世纪90年代“失落的十年”。曾经的天下无敌,就此陷入了萧条。对于中国来说,任何这样的结果都将是一场灾难,这一点不言而喻。与此同时,如果没有从高收入国家向其它国家的巨额净资本流入,我们很难设想全球经济会有一个稳健的结构。不过,如果全球最大、且最成功的新兴经济体也是最大的资金净输出国,我们也很难想象这种情况会发生,而且可以持续。

我们所需要的,是找到这些亟需进行的全球调整的路径。这将不仅需要合作的意愿——眼下似乎严重匮乏,还需要在国内与国际改革方面更丰富的想象力。我很想做一个乐观主义者。但我不是:一个充斥着以邻为壑政策的世界,最不可能会有美好的结局。

译者/何黎

******************************

Currency wars in an era of chronically weak demand

“We’re in the midst of an international currency war, a general weakening of currency. This threatens us because it takes away our competitiveness.” This complaint by Guido Mantega, Brazil’s finance minister, is entirely understandable. In an era of deficient demand, issuers of reserve currencies adopt monetary expansion and non-issuers respond with currency intervention. Those, like Brazil, who are not among the former and prefer not to copy the latter, find their currencies soaring. They fear the results.

This is not the first time for such currency conflicts. In September 1985, now 25 years ago, the governments of France, West Germany, Japan, the US and the UK met at the Plaza Hotel in New York and agreed to push for depreciation of the US dollar. Earlier still, in August 1971, the US president Richard Nixon imposed the “Nixon shock”, imposing a 10 per cent import surcharge and ending dollar convertibility into gold. Both events reflected the US desire to depreciate the dollar. It has the same desire today. But this time is different: the focus of attention is not a compliant ally, such as Japan, but the world’s next superpower: China. When such elephants fight, bystanders are likely to be trampled.

Here there are three facts, relevant to today’s currency wars.

First, as a result of the crisis, the developed world is suffering from chronically deficient demand. In none of the six biggest high-income economies – the US, Japan, Germany, France, the UK and Italy – was gross domestic product in the second quarter of this year back to where it was in the first quarter of 2008. These economies are now operating at up to 10 per cent below their past trends. One indication of the excess supply is the decline in core inflation to close to 1 per cent in the US and the eurozone: deflation beckons. These countries hope for export-led growth. This is true both of those with trade deficits (such as the US) and of those with surpluses (such as Germany and Japan). In aggregate, however, this can only happen if emerging economies shift towards current account deficit.

Second, private sectors are working in just this direction. In its April forecasts (soon to be updated), the Washington-based Institute for International Finance suggested that this year the net flow of external private finance into the emerging countries would be $746bn (see chart). This would be partially offset by a net private outflow from these countries of $566bn. Nevertheless, with a current account surplus of $320bn as well, and modest official capital inflows, the external balance of the emerging world, without official intervention, would be a surplus of $535bn. But, without the intervention, that could not happen: the current account must balance the net capital flow. The adjustment would go via a higher exchange rate. In the end, the emerging world would run a current account deficit financed by a net inflow of private capital from the high-income countries. Indeed, that is precisely what one would expect to happen.

Third, this natural adjustment continues to be thwarted by the build-up of foreign currency reserves,. These sums represent an official capital outflow (see chart). Between January 1999 and July 2008, the world’s official reserves rose from $1,615bn to $7,534bn – a staggering increase of $5,918bn. This increase was, one might argue, a form of self-insurance after earlier crises. Indeed, reserves were used up during this crisis: they shrank by $472bn between July 2008 and February 2009. No doubt, this helped countries without reserve currencies cushion the impact. But this use of reserves was a mere 6 per cent of the pre-crisis level. Moreover, between February 2009 and May 2010, reserves rose by another $1,324bn, to reach close to $8,385bn. Mercantilism lives!

China is overwhelmingly the dominant intervener, accounting for 40 per cent of the accumulation since February 2009. By June 2010, its reserves had reached $2,450bn, 30 per cent of the world total and a staggering 50 per cent of its own GDP. This accumulation must be viewed as a huge export subsidy.

Never in human history can the government of one superpower have lent so much to that of another. Some argue – Komal Sri-Kumar of the Trust Company of the West, in Tuesday’s Financial Times, for example – that such management of the exchange rate is not manipulative, contrary to views in the US Congress, since adjustment can occur via “changes in domestic costs and prices”. This argument would be more convincing if China had not worked hard and successfully to suppress the natural monetary and so inflationary consequences of its intervention. In the meantime, the inevitable adjustment towards current account deficits in the emerging world is being shifted on to countries that are both attractive to capital inflows and unwilling or unable to intervene in the currency markets on the needed scale. Poor Brazil! Could we even be seeing the starting gun for the next emerging market financial crisis?

John Connally, Nixon’s secretary of the Treasury, famously told the Europeans that the dollar “is our currency, but your problem”. The Chinese respond in kind. In the absence of currency adjustments, we are seeing a form of monetary warfare: in effect, the US is seeking to inflate China, and China to deflate the US. Both sides are convinced they are right; neither is succeeding; and the rest of the world suffers.

It is not hard to see China’s point of view: it is desperate to avoid what it views as the dire fate of Japan after the Plaza accord. With export competitiveness damaged by its soaring currency and pressured by the US to reduce its current account surplus, Japan chose not the needed structural reforms, but a huge monetary expansion, instead. The consequent bubble helped deliver the “lost decade” of the 1990s. Once a world-beater, Japan fell into the doldrums. For China, self-evidently, any such outcome would be a catastrophe. At the same time, it is difficult to envisage a robust configuration of the world economy without large net capital flows from the high-income countries to the rest. Yet it is also hard to imagine that happening, on a sustainable basis, if the world’s biggest and most successful emerging economy is also its largest net exporter of capital.

What is needed is a route to these needed global adjustments. That will demand not just a will to co-operate that now seems sorely lacking, but greater imagination about both domestic and international reforms. I would like to be optimistic. But I am not: a world of beggar-my-neighbour policy is most unlikely to end well.

沒有留言:

張貼留言